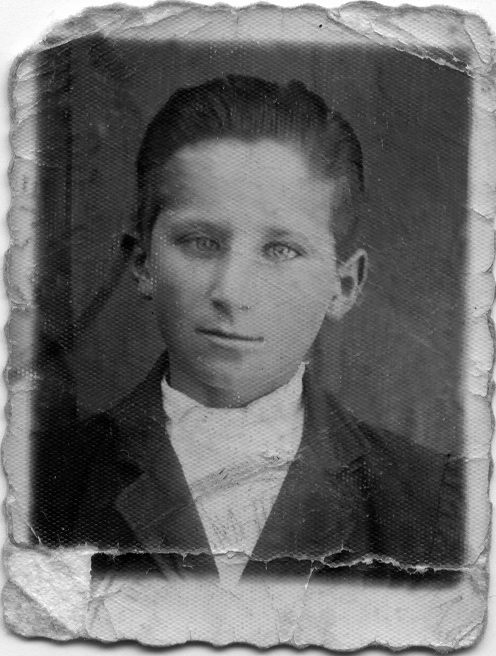

It has been eight years since the passing away of Milan Bastašić, my father, a former eleven-year-old boy, a Jasenovac concentration camp inmate.

On this occasion, I am transcribing part of his testimony, published in 2010. in the book „Bilogora and Grubišno Polje 1941-1991“, which he authored.

At the age of less than twelve, as a boy classified among men, he was transported to Jasenovac concentration camp in a cattle wooden wagon from his native Grubišno Polje.

Due to a combination of circumstances that cannot be accidental, after two months, as the patient fell ill with typhus, he returned home. He survived. The only surviving boy- Jasenovac camp inmate from Bilogora, Western Slavonia, Croatia.

I am going to death, I am aware of that, but there is no final „act“ on that journey to death. And, in fact, he, that „act“ – it is death.

We get up in the morning, it’s cold, everything is damp, the „celta“ (something like tent wing) is white. I change my pants – the muddy ones in my bag, and another I put on as a coat.

„Assembly“ for breakfast.

Breakfast passed. I go back to the barracks to my bunk. I see a few boys over there on the left. Some are from Bilogora. I didn’t know them before, but that’s where we met.

They were Milan Sužnjević from Velika Barna, Nikola Pelinović from Mali Grđevac, the previously mentioned Stojan Dardić and some others whose names I no longer remember. The rest are those who were previously brought from Kozara, Kordun and Banija.

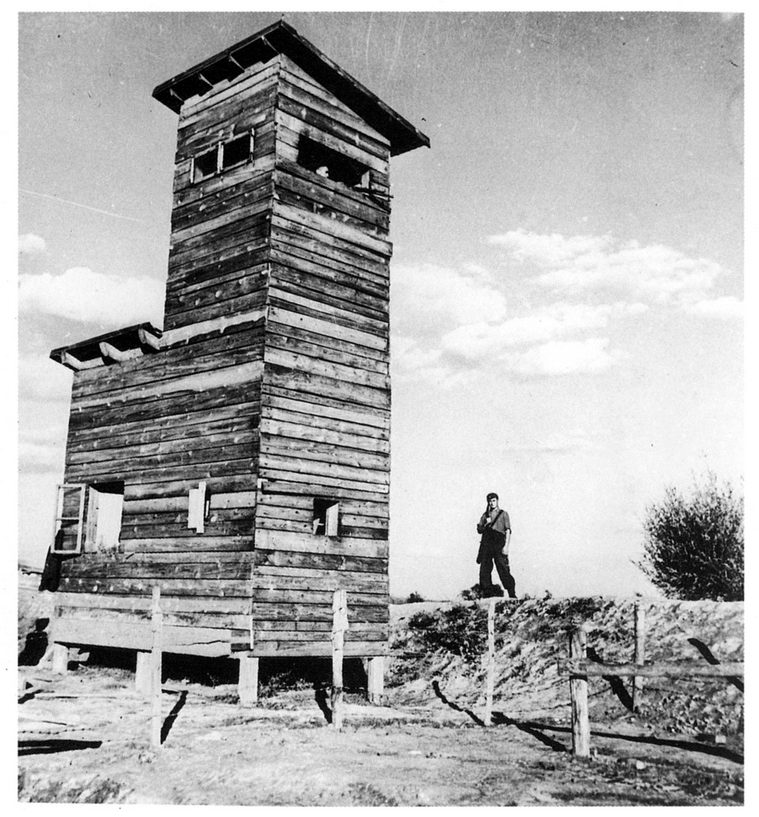

We are all scared because word got out that sick children were killed, butchered. Some are comforting themselves that we will go to Donja Gradina, Bosnia, buy fruit and eat our fill. No one talks about the death outcome, although it is present in everyone in its own way. With all that, this uncertainty makes us numb.

I am in a special state. I sense the end, I am almost aware of it. Farewell to life… However, fear is absent. I guess because there is no other way out. There is only death. Well, it will come at any moment in the form of an Ustasha call „to assemble“. And that’s the end of the first phase. A section of road to Sava or Gradina follows. And death itself, the act of dying – that is not clear to me, I have no idea about it. I know what death is, but how it comes about here, with what, what it is – I don’t know, I have no idea about that „act“. That „act“ is not present in my ominous thinking.

They talk a lot, often, almost constantly here about death, about slaughter, about killing… I also saw the shooting of the sixteen. I saw that poor old man, Joca, whom they also said ended up in Sava. On the embankment, I saw Ustasha on a horse, how he killed a man with a club, so, they say, they buried him in the embankment.

I saw how the Ustasha „jokingly“ forced that poor Adam (Maxim?), by manners, was called a madman, „to lie down“. He is on his knees, crying and begging: „Oh, don’t, oh, please!“ That was fun in the camp for some Ustashas – to order a prisoner to lie down and shoot him, usually in the head. I didn’t see that, but it was often talked about. Well, poor Adam knew that too. They say that after that he hid somewhere, that the Ustashas were looking for him „for fun“, but they didn’t find him until he appeared on his own (he got out of some wood, planks).

On one occasion, I saw a young man (16-17 years old) crying loudly: „Oh, they killed my father, they killed my father! Oh, what am I going to do, they killed my father“! He shouts pitifully and gesticulates, no one tries to comfort him. Some Ustasha came up and said: „Well, who told you that?“ They didn’t kill him, he went to work.“ The poor young man continues, loudly and stereotypically: „Oh, they killed him, they killed my father“! Ensign „101“ arrives on horseback, stops and listens, then says: „Well, they didn’t kill him, fuck him.“ Why are you yelling“? „Oh, they did, they did!“ They killed him“! „Take him there to his father“, commanded „101“, „show him his father“. The Ustasha took him by the shoulder, and it was clear to us what would happen to him. The poor young man in his misery could not even imagine that the Ustasha would either kill him or, which was done far more often, slaughter him.

I guess in those conditions their reasoning is absent or in those conditions normal reasoning cannot make realistic conclusions. As soon as I heard the painful wailing of the poor young man, I knew what was going to happen to him. I concluded that he shouldn’t have exposed himself like that, that he had to think about what might happen to him.

Before that event, a few nights before going to bed (darkness falls quickly at this time), I sat in the shack and cried wondering: „Will we ever all meet at that kitchen table of ours „? Knowledge and time have convinced me, even a year ago, that my father and brother, and all those who were driven away with them, were killed by the Ustashas in Jadovna. But I assumed they were also at that table.

As for my mother and sister, I didn’t know where they ended up. That fixing of the kitchen table must have been imposed by the feeling of hunger. Here, let’s gather at that table.

And loneliness also took its toll. I lived through the disappearance of Pera and Uncle Toša, and the news of Milan Adamović’s death was still fresh. Well, all that did not „conjure up“ to me one or more ways that I will end up soon. They are forcing us to die, we are going to a place where we will no longer be alive. It has to be done, they are forcing us to disappear there. That’s understandable, that’s exactly what we’re waiting for in an ominous omen. But, in me there is no „act“ of disappearing, it is completely absent. I am going to death, I am aware of that, but there is no final „act“ on that journey to death. And, in fact, he, that „act“ – it is death.

„Children in the assembly“, the voices of the Ustashas are heard. The voices are not heard in front, but down there in our barracks. We’re leaving quickly. It’s a long way to my bed, so since I don’t want to be the last to go out, instead of my rag, I take some kind of quilt from someone’s bed. Because it’s winter, it’s cold, wet, it’s raining, and the blankets are left over from sick children who were killed a day or two ago.

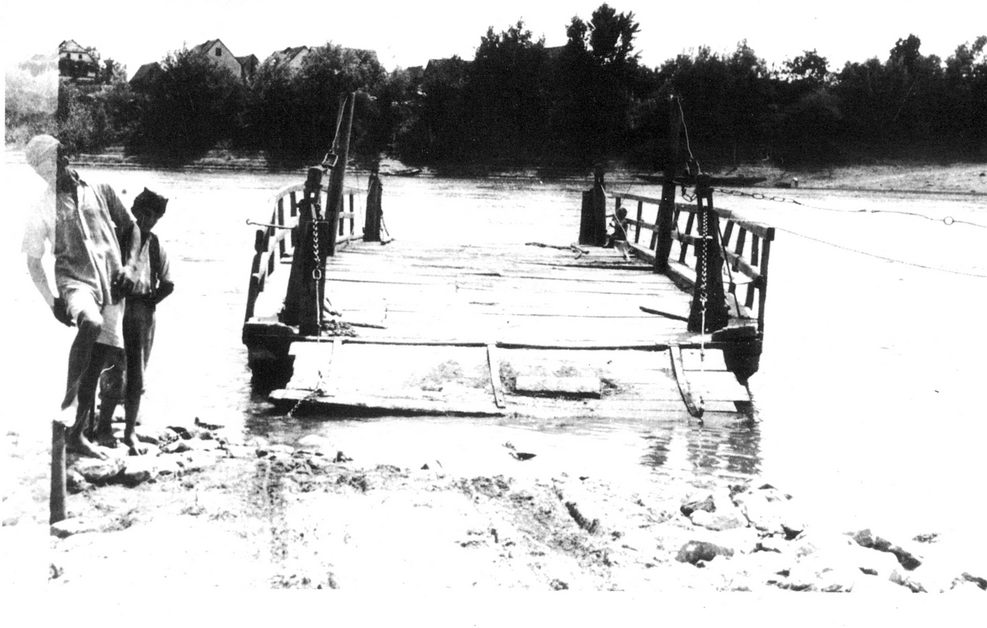

They line us up in the mud. There are five or six Ustasha around us. They order us to stand in two lines, in two rows. I’m holding that quilt on my shoulder, and Ustasha stands in front of me and says: „What do you want with that?“ „Well that’s mine.“ I need it“, I answer. „You won’t need anything in half an hour.“ All of your throats will be white. Throw it“! I throw that quilt behind my back in the mud and keep silent.

We were there a little longer when he ordered a „leave“. We split up – some in the barracks, some walking around the barracks, some going towards the kitchen. Someone said that there are plenty of sweet turnips in the bins outside the kitchen. A few of us go there, we take out pieces of turnips. I try to eat, I lick it, but it doesn’t work. I throw it back and go to the barracks. Some are lying down, others are standing in the barracks, some are outside. We are already very hungry. A few of us go to the turnip bins again. We try again, but it doesn’t work. We return to the barracks.

Here it is – „assembly“ again. We line up and wait. The same Ustasha again. They walk around us. Another one arrives and they ask him: „Shall we tie“? „Don’t, they won’t be ready for another hour or two.“ Give them a ‘leave’”. We part again, walk, lie down a bit. Everyone is mostly silent. What remains unclear is: „Should we tie them“? There was a talk about whether it applies to us. The question follows: „Why would they tie us up“, but there is no answer.

„At least to give us something to eat“, some comment, then they return to the bins with sweet turnips. Now we are discussing how it is that turnips are so sweet and can’t be eaten. I’m thinking for myself, I know that (especially Pemci) they used to make syrup from that turnip, but it’s not good for eating. It’s been quite some time. It’s foggy, gloomy and dark.

A few more Ustashas are coming towards us now, when, from the embankment five or six steps behind us, a man asks: „Who is Milan Bastašić?“

„It’s me,“ I answered somewhat reservedly, in a low voice.

„Come on, hurry up,“ he says, and I head towards the embankment. He waits for me. He goes before me, I follow him.

I hear that the Ustashas are arguing about the „assembly“ and the line-up. Nothing applies to me. They didn’t even ask where he was taking me. All those details remained deeply engraved in my memory. But, even though I was aware that all those who remained then went to their deaths, I never thought about the final act of their terrible irreversible journey. Everything ended with the moment I left for the embankment.

It was only many years later, after I read Dr. Nikola Nikolić’s books Jasenovački logor smrti and Kozaračka djeca , in the latter I found a text that reminded me of the question of the Ustasha who approached the assembly while I was still in it: „To tie“? Then, since we were given a „leave“ again, we children could not explain to ourselves that it applied to us. We could not find an answer to the question – why would they tie us up?

Nikolić writes about the actions towards the children, who were waiting for liquidation-slaughter in the assembly, and about the events in it:

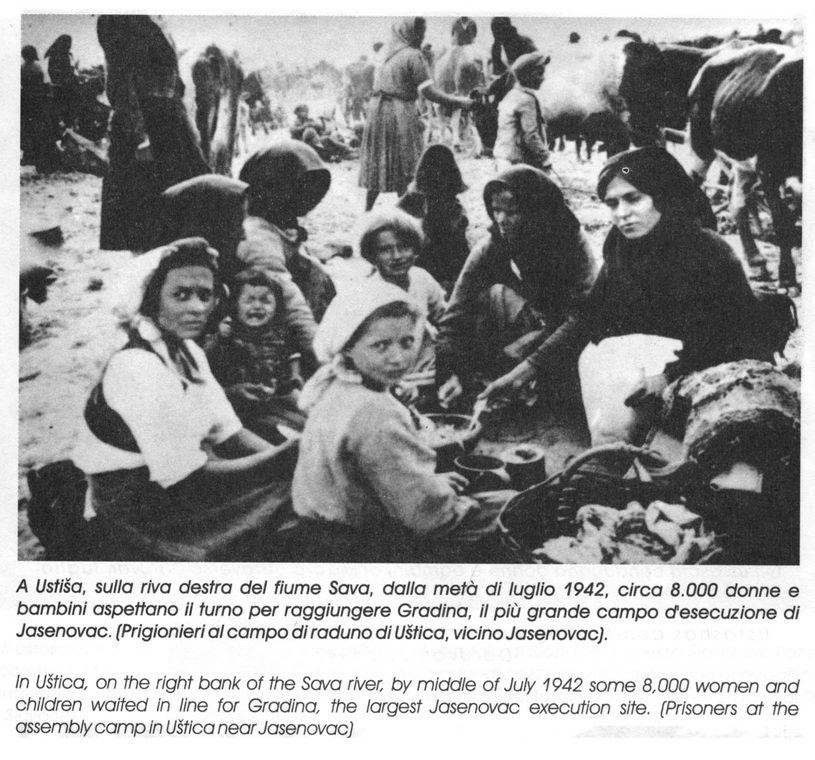

„The moping teachers retreated to the artificial lock of Jurica Pandić and Dragec Plečko and stood peering out from it, shaken by the knowledge of what would happen next with the children. A little later, the Ustashas surrounded them and started tying their hands behind their backs with wire. Then one of the most indescribable and shocking events happened in the camp. The children started screaming, shouting, calling for their teachers, God, the devil, their father. Through that horrible shouting, crying and screaming, you could also hear the shouts and curses of the Ustasha and the slapping of frantic children. Precisely at 5:00 p.m., in the twilight of October 15, 1942, they took the children, already half dead from fear, towards the Sava, to the ferry to Gradina.

A procession of children tied with wire passed through the camp gates with horrible whining, wailing, cursing and cursing, leaving six children’s corpses in front of the command which were quickly picked up by camp gravediggers“.

Dr. Nikola Nikolić describes such scenes on several occasions, with dates, numbers and witnesses. According to those descriptions, it can be concluded that the train of child detainees (from which Žiga rescued me) was slaughtered on October 29, 1942.

(From the book: Milan Bastašić: Bilogora and Grubišno Polje 1941-1991. )

Prepared by: Dušan (Milan) Bastašić

E mail: [email protected]

President of Jadovno 1941. Association, Banja Luka, Republic of Srpska