Great efforts reveal the truth

I join all people who in autumn 1985 read articles in “Novi list” from Rijeka on SLANA, titled HELL IN A ROCKY DESERT and I thank comrades Boris Ostojić and Mihajlo Sobelovski for finding a way and making effort, four decades since the terrible events in the Ustasha concentration camp SLANA on Pag, to collect what little material could be found, verified and used as evidence, judgment or legend created from evil deeds unseen in our age until then.

I equally thank editors who, by publishing this material on the pages of “Novi list”, in a suitable way opened an unlimited survey on this horrific event. This horrific, but compared to the tragedies, still small material, just a piece of information on the camp, deserves more detailed research and needs to be completed by everyone who knows anything about it or possess any material evidence, but taking precautions and diligently separating the truth from potential fabrications, bragging, naivety, augmentation or deception which in such cases is very probable.

Each and even the smallest detail from those days connected with this location on rocky Pag can be valuable for depicting and revealing the period that must not repeat ever again.

As we can see from the material already published, the research into the true facts on the SLANA camp is a tough nut to crack, but we need to say that this topic has been covered before, but in a modest and random way.

Piety towards SLANA

For years I have been coming back to this topic, but because I was unable to complete the whole picture I was afraid to publish it. I can give you several examples of obvious care for this important holy place on the island that we, the people of Pag expressed over time.

Immediately after the Ustasha left the camp (1941), I went to this site (and I will talk about it later in more detail) with a group of farmers and fishermen from Pag (who later on became soldiers of the People’s Liberation Army – Narodnooslobodilačka vojska, NOV).

Then in 1947 and 1948 I led groups of Pag people, with a lot of youth from youth groups, together with former soldiers. We were also joined by the town brass band. For that occasion we laid wreaths on dug out graves at Furnaža over Malin. I will describe to you an image that was within us at the time, so other people would learn from it: it was a moving sight to watch young people approaching the destroyed graves with obvious emotions, constantly being careful not to disturb the silence in that deaf wilderness by moving a stone or by kicking a lump of earth with their shoes.

People of Pag made a similar visit in the 60-ties. Teachers tell me that the custom still exists and that the visit is conducted on a regular basis even today. Schoolchildren from Pag and Novalja come with boats to this unfortunate site for piety and an obvious history class.

Last year I witnessed how children from the Croatian coast, who traditionally gather for a festival of youth culture and art named “October in Novalja”, chose a delegation that would visit SLANA and lay a wreath for the victims.

SLANA has not been neglected

As far as twenty years ago, people from Pag started collecting money to build a monument on this site. Initially, we entrusted this to the Fighters Association (partisan fighters, members of the People’s Liberation Army) in Pag and its head at the time, Slavko Maržić. With his effort, this activity had good initial results. Unfortunately, it stopped for several reasons, one of them being financial inability of the Pag community to tackle this project that requires expertise and large finances. We even went forward and asked the public for help, but this attempt failed as it started due to poor response.

Under the new leadership of the Fighters Association, led by Nikola Bistričić, we decided not to build a large monument for the time being, but to at least mark this rocky area with a sign on the top of a rock above the sea in Suha, at the beginning of the SLANA camp. Bistričić was persistent enough to see this through, just as he, at the same time, managed to realise the decoration of the Partisan cemetery and to have the street where the Italian people’s hero from Pag, Antonio Danielli – “Pino da Zara”, bear this name.

The Ustasha did not expose us

During the general misfortune of those days there was an event connected to the SLANA camp that had a happy ending, which was a starting point for unmasking the Ustasha rule of terror in our area. Oren Ružić[1] and I, while the SLANA camp was still in function, got our hands on a printing machine from the offices of the Municipal Court in Pag. (Only Ivan Sabalić, a steward at the time, “Franac” and Court President Milan Nožinić, who was saved while he was on his way to the camp, sent there as an Orthodox Christian, knew for what purpose was the printing machine used. Although they knew, they never saw our work!). The Court was next to the Italian Command, Carabinieri and Ustasha gendarmerie were across the road in what today is Hotel “Smokva”. On the third floor of the Court building, in the Uhlinac Street (today named after our third comrade in the group, Vinko Fabijanić Aleksa), we typed the matrix for fliers in which we wrote about the disgraceful and monstrous deeds on our Island – about SLANA. The whole flier was dedicated to that crime which was happening right before eyes only few insurmountable kilometres away.

I need to remind you that these were the days during which, in our distant and lonesome Pag, the uprising was wanted but it was still trying to get its shape!

One afternoon while we were clumsily typing text into the machine, we suddenly heard that someone entered the building and was rushing up the stairs. The wooden stairs were screeching heavily under obviously military boots. I quickly took out the paper from the machine and took whatever I could find on the table and tucked it under my shirt. At the same time Ustasha from Pag named Herenda charged into the room and went straigt at us, towards the table. While he was going through papers and opened the drawer twice, he asked us questions which we did not really answer, but rather calmly told him that we were preparing to go back to school and were writing to out schools in Zagreb to ask them when and where to apply. So we were learning how to type in order to write letters!

He did not believe us at first. After he had taken the blank papers from the drawer again, he suddenly turned and left the room.

The Ustasha for a single moment did not think that Ružić had a pistol in his pocket which he was to fire if the Ustasha found the flier.

We were, in fact, saved because this village cop, after following as and seeing us enter the Court, lost his patience and hurried to discover what we were doing there. If he had let us continue our work for a while he would have not been so lucky, and perhaps so would not we!

In my book of poems written during the war, published under the tile, CHASE AFTER ME ACROSS THE ISLAND, on page 9 there is a hand print over which there are hand-written words TODAY MY POEM DIED! GLORY! GLORY! MAY IS FULL OF SUNSHINE. AND DEATH.

This surrealistic vision of death that I experienced as a young man remains my early and modest commemoration for the innocent victims of SLANA. The name of the poem is May.

TO THE VICTIMS – OF SLANA!

Regardless how much the author of this book in his young years was passionate for poetic surrealism, during those days surrealism was not the only form of action I took. While talking about the mission to defend the country and clear our face, which we embraced as our destiny, and efforts for this mission were increasing in this area, I will mention only one more personal event that takes us to the very beginning, in the time while there was still smoke rising from the SLANA camp.

People say and write how I placed the first memorial for Slana victims, right under Ustashas’ noses (we should call it a memorial challenge).

I made a resolute suggestion to my SKOJ (Alliance of Communist Youth of Yugoslavia) group that we need to place a wreath for the Slana victims on the public cross and that I was ready to do that. I did not have to persuade my comrades for long. The plan was accepted very quickly. We were to make it from blackthorn branches, paint it in silver and place black ribbons from each side two metres in length with golden letters saying:

TO THE VICTIMS – OF SLANA

Only one merchant sold black ribbons, but we believed he would say nothing, because he did not favour Ustashas. We have made the plan in fine details, because the wreath was possible to put up secretly only before night time, i.e. before the curfew. That meant appearing several minutes before the curfew for a walk along the coast where Italian officers used to walk and who knew us well, and also Ustashas and their informers, who knew us even better, and then sneak out for a moment, move the hidden wreath to the cross, tie both the wreath and the ribbons and show up at the coast for a walk in just two minutes, as if we had been walking the whole time. We obviously tried out the plan a couple days before (without the wreath).

We made the wreath in the house of Josip Pančoka at the very south coast of town, but, as luck favours the brave, Joško and I managed to carry it through the streets without anyone noticing anything (which was later on confirmed by the police!), and which is quite strange for streets where everybody knows everything and sees everything.

The next morning, as we had expected and wanted, we impatiently spread the word. There was chaos amongst the people and Ustashas. The people were rushing to see it with their own eyes, and Ustashas were in the hurry to take it off.

The local Ustashas had a lot of problems taking down the wreath for the dead because of the people. We consider taking down such a wreath a great shame and sacrilege! However, forced by their political views, they were left with little choice but to take it down around 11am.

As I pretended to be there by accident, I tried to think of ways to put up obstacles. As one of the bystanders I told them that it was not a nice thing to do. What would the people who watch say? That they were hurting religious feelings, that the families of the dead are probably somewhere here, and how would they feel if someone took off their family wreaths, that they would be condemned by the church and priests when they find out, etc. I tried to extend the life of the wreath for at least several hours more, because a lady guest from Osijek came with a camera (which of us would have a camera at the time!) and we needed to wait for the sun to move to the side in order to take a picture. She took a photo at the last minute, but it did not come out well).

In all their anger, the Ustashas took the wreath to the District Branch Office in Pag as evidence and gave it for further investigation. However, they never managed to discover it had been us! The District Manager at the time was our collaborator! We have already said that he had kept the wreath until Italy capitulated when it was lost in the commotion.

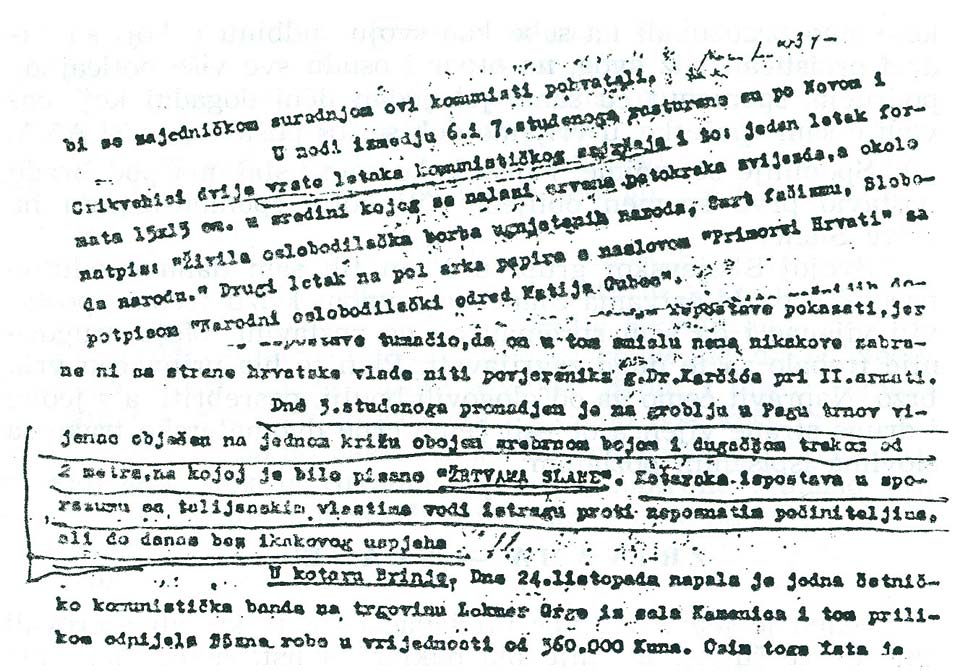

However, the Ustashas themselves managed to preserve a memory to that real (maybe the first Yugoslavian!) public mark for the victims of this country. Recently, while rummaging the archives, I found proof that each crime still leaves a trail in an Ustasha police report, sent by Great Governor of Vinodol and Podgorje to his Poglavnik. Between the item talking about wine and item number three talking about “Chetnik communist gang…” there is a record that filled me with joy and memories on my youth:

“On November 3, a thorny wreath was found at the cemetery in Pag hanging on a cross and painted with silver paint and with a 2-metre ribbon on which clearly read “TO THE VICTIMS OF SLANA”. The District Branch Office in cooperation with Italian authorities leads the investigation on unknown perpetrators, but we had no success so far!”

First records on SLANA

If our wreath with a two-metre ribbon and our (SKOJ) fliers distributed all over Pag amongst Italian soldiers of the Pag Garrison, and two Italian reports (by Dr. Finderla and Dr. Santo Stazzi) from 1941, are not considered to be the first records on Slana but more symbols of resistance and a part of the uprising (and the Italian report considered the result of a disciplined and well-conducted mission), then the people who informed the public first were representatives of Jews from Mostar (town in southern Bosnia and Herzegovina). In January 1942 they wrote a long memo on the position of Jews at the time on the territory of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia and sent it to following address: “General, Commander of the Cacciatori delle Alpi Division – Mostar”. In the memo they presented him with a difficult position of Jews and what they had been through and where they had been killed. In that document, on page 9, they talk about a location, getting the name wrong, but still they mentioned it: “… in the woods close to Gospić and Pag”. They knew the approximate direction where their loved ones disappeared, but they probably did not know the exact name of the dreadful site – Jadovno and Slana.

“… In the beginning the Ustashas took them to do forced labour in the woods near Gospić and Pag, where the prisoners went through terrible torture, no roof over their heads and without suitable clothes, and they were fed with minimal food portions. And when they heard that that area would be handed over to the Italian army, Ustashas killed hundreds of prisoners because they did not have enough time to evacuate them all and from fear the prisoners might get released. The rest of them they moved to the Jasenovac concentration camp.”

Maja Narić, in an article in the (former) VUS (Vijesnik u srijedu – Wednesday Herald), was lucky enough – if you could call reporting on crimes and criminals lucky – to be amongst the first journalists to report a horrifying story from the mouths of criminals heard at the Zadar County Court where seven of Ustashas were tried – Baljak and others – the Slana butchers. The article was published in issue from June 10, 1953 and VUS published their masterpiece article with pictures and partial statements from the murderers which made the reader’s skin crawl.

A couple of years ago I told “Večernji list“(Evening paper) correspondent Ivo Palčić from Pag, a student at the time, everything I knew about the camp and he published his report in sequels. It was the first time that the public heard about a document made by an eyewitness, Italian officer and doctor Santo Stanzzi, about exhumation of victims in Slana, on the number of the dead found in Furnaža (above Malin) and other sites, testimonies on the way they had been killed, etc.

The core of the report from “Novi list” in 1985 is largely and with its most convincing part based on material on Slana that had been piling up. Lacking new elements, from formless components we used what could have been considered most believable.

One of more reliable materials that were waiting to be published was given by former camp inmate Josip Balaž „Joža“ in 1979, in Pag in the office of the Fighters Association, to N. Bistričić, S. Maržić and me. In order to get the most reliable statement from him we had invited Blaž to come from Daruvar and be our guest in Pag. We took him to the scene in order to establish what would be the best steps forward. All the credits for finding Blaž, a men nobody knew existed or that he had survived the camp, go to N. Bistričić who had not slept until he found an authentic witness to confirm what we had known. We could have moved forward only if we had solid data.

I also think that they should have started writing the report in “Novi list” with less confidence and with greater care. But I do not hold it against them! This difficult work had to be started, go bravely, and the real story will appear after possible mistakes have been removed. In fact, in a work like this one, you cannot know what is the more right thing to do, to wait for a long time (and it has been too long a time) or to publish it bravely. Both have good and bad sides.

As we are talking about initiatives that always start activities, it is worth mentioning one that has ended.

During one of my stays in Belgrade fifteen years ago, at that time retired, now deceased, Pavle Babac, born in Šibuljine hamlet (village Tribanj under Velebit), told me that he had written a proposal to the Zagreb newspaper “Vijesnik” to tell them some facts on the Slana camp. He did not receive a single answer from “Vijesnik”. I need to stress that Babac was from a village whose all Orthodox Christian inhabitants were taken to the camp and that he had been writing books on his home area under Velebit. It was a great mistake not to support Babac at that time in his willingness to testify about Slana and invoke a wider interest and more testimonies. In a brief conversation that we had, he told me that his first cousin Aleksa Babac, 12-year old girl Marija and his aunt and grandmother Jelena were killed in the camp. With warm feelings he also told me about priest Don Ante Adžija who was shot by Ustashas, and a priest from Kruščica, Don Lovro (I forgot his surname) and who was the President of the People’s Liberation Committee (NOO) in Starigrad. The names of people taken from Šibuljina to Pag (to the camp or straight to Furnaža) are written in a monument in Šibuljina. Only in 1986, thanks to his family, did I come into possession of a manuscript written by Babac titled VELEBIT AREA 1941 – 1945. We are going to go back to his words later.

Irrefutable evidence

Several years ago in the Revolution Museum in Zagreb I found and identified photographs that were published in the report in Novi list last year. People at the museum did not know where to classify these photographs because they were not marked. It was obvious that the photographs were in the hands of someone who knew what they were about, because I found them in a pile together with a facsimile of a record taken on April 2, 1946 by the War Crime Commission for Croatian Coast.

This record is a very detailed testimony of an Italian colonel, Pietro Fioretti, born in Viterba, Italy, an active officer of the Guardia della Frontiera (G.A.F.) based at Trieste, which was under the command of the 5 Army Corps with headquarters in Crikvenica. As a colonel, Firetti commanded the Sector 27 of G.A.F. (based in Rijeka), with units deployed also on the island of Pag (1941) with around 150 Italian soldiers. We can put all of our trust into his statement when we know that Fioretti was an anti-fascist and that one of his sons was taken by the Germans and died at a German camp and his other son died fighting with the Allies in Africa. After the liberation, Fioretti was the Secretary of the “A. Pasinotti” School in Rijeka.

Speaking about the photographs, I assume they might be the photographs mentioned by a Pag photographer, Toni Vidolin and his daughter Rajka. These photos were, allegedly, given to Bilić[2], then ZAVNOH (State Anti-Fascist Council of the People’s Liberation of Croatia), then Radetić[3] and in the end the Revolution Museum in Zagreb. If we look at Fioretti’s record more closely, we see a new hope that these photos could lead us once again to the right place, i.e. to the originals and similar photos, reports and other types of documents on the camp. Fioretti’s statement, just as the statement by Marko Paro Vidolin “Kiža“ confirms an encouraging fact for this case; that the Italians watched and knew what was going on in SLANA, just as they knew what was happening in Lika, Kninska krajina and Dalmatia. It was a part of their programmed policy: stay on the side and help the destruction of this country in every step.

Colonel Pietro Fioretti’s statement

In the beginning of his statement Fioretti himself starts to question the relationship between Fascist Italy and the “friendly” country (NDH). While talking about stationing Italian units in Pag, he mentions that according to the agreement with Pavelić the island of Pag belongs to the NDH and he wonders what Italian military doing on a friendly terrain is: “… The garrison in Pag was instructed to act like guests and friends in a friendly country”. Then he asks himself what is the point in the troops being there, adding that he “often wondered about that”. While talking about local tasks and how well the Command was informed, he clearly accuses Italian military and political circles for being accomplices in crime – they knew about the crime but did nothing to prevent it!

In order to make his claims clearer in regards to the behaviour of Italian occupying force, he tells about his acquaintance with whom he had private conversations, Captain Paolo Beroli, born in Trieste, a fascist sympathizer, who was the commander of the Italian garrison in Pag during the Slana slaughter: Bertolini was friends with Ustasha officers and organizers. Later on we saw him in a picture how he visits graves and pits in Slana during the exhumations and cremation of remains!

Due to its importance, we give the record from the questioning of Italian Colonel Pietro Fioretti in full:

“Witness, Fioretti, Pietro, born in Viterbo, 58 years of age, married, father of one, now the Secretary of “A. Pasinotti” primary school in Rijeka, residing in Rijeka, 8 Via de Amicis, warned to tell the truth, gives the following statement:

Until the capitulation of Italy and 8 moths after that I was an active officer of the Italian Army. My unit was Guardia all Frontier from October 1, 1937 to April 1, 1942.

The GAF Headquarters were in Trieste commanded by the following officers: Searoni until August 1940, General Russi, 55 years of age, medium height, light gray hair, until October 1941, stationed in Ilirska Bistrica, then General Bazio Vono, born in Monferatto, same town where the Trieste prefect was born, 57 years old, short and overweight, slightly bald and with grey hair, until April 1, 1942.

The GAF Headquarters were under the command of the 5 Army Corps in Crikvenica, commanded by Army Corps General Riccardo Baloco, born in Piemonto, 55 years of age, 178 – 180 cm tall, grey hair, no moustaches or beard, Commander from June 10, 1940 to the end or early March 1942.

Under the command of GAF were sectors XXV with headquarters in Sv. Petar on Kras, XXXVI in Ilirska Bistrica and XXVII with headquarters in Rijeka.

Each sector consisted of infantry, artillery, pioneers and machine gunners. XXVII sector had 5 battalions (5 grupi di esposaldo) 7 batteries and one pioneer company (genio).

In 1941, one independent company with around 150 soldiers was stationed (formed) near the island of Pag and one third of soldiers were in Novalja. The Italian name for this unit of the XXVII sector was Compagnia autonoma di formazione distacamento a Pago, and the name for the Novalja garrison was Plotona distacato a Novalia.

The soldiers wore green markings with Alpine hats with no feathers, and grey ties.

The first commander of the independent company of the XXVII sector in Pag was Captain Paolo Bertoli, around 34 years of age, tall, blond-chestnut hair and aquiline nose, from the establishment of the unit until at least April 1, 1942, when I was transferred to the command of the 2 Army in Sušak, to the Operations Department. I thought that everything was alright at the time and I heard nothing about preparations for the camp in Slana, nor that they were bringing people there.

The garrison in Pag were instructed to act as guests and friends in a friendly country. What was the purpose of this garrison in Pag, both military and political, I do not know, and I often wondered about that. I know that the garrison in Pag, just as other garrisons, was tasked to maintain order, control the movement of people and issue passes. Considering all this, this garrison had to inform their superiors on the events in the area, and also on the events concerning the camp in Slana. In terms of this information, the garrison was directly responsible to the Division Command of the 5 Army Corps in Crikvenica, which was under the command of II Army in Sušak. Through this chain of command, the Pag garrison received its instructions, and in the same way the reports reached the II Army command in Sušak. So, according to his duty, Captain Bertoli, as the garrison commander in Pag, had to inform II Army command on the events in Slana. Such a report had to go through the division and 5 Army Corps to the Civil Affairs Office (Ufficcio afferi civili) of the II Army. Whether he did that or not I was not authorised to know, although I was the commander of XXVII sector. It is possible that such a report might have been delivered to the Operations Office (Uffizio operazioni) of the II Army. I must say that Bertoli told me about the events in Slana after April 1, 1942, when I was no longer the commander of the GAF XXVII sector. He told me that around 4000 thousand people were brought to Slana and were killed and thrown into the sea, or slaughtered and buried in a large pit. According to him, some of them were daughters of Yugoslav officers who were first raped, than killed and thrown into the pit. He also told me that some of the persons were thrown into the pit alive and that he heard their cries.

I think that the Zara Division was subordinate to the 5 Army Corps at the time. Who was the commander of this division during the slaughter in Slana I do not know.

From the start I was a sympathizer of the Partisan movement. Partisans met at my house. My second son was also a Partisan. That is why he was arrested by the Germans and taken to Germany as a prisoner, where he died. My first son died at Casino in combat as an active Italian officer under the command of Allies, fighting the Germans. I was also under a threat of being arrested in March 1945 by the Germans, because I was a Partisan sympathizer.

(County War Crimes Commission for Croatian Coast, No. 476/46, February 2, 1946. Signed by the questioned person and members of the Commission).

Two-faced role of Capt Bertoli

I knew Captain Bertili personally and I contacted him twice. In a notebook we found in the Italian command in Senj after the capitulation of Italy, and which was sent from Pag in 1941 with other information obtained by the Italian intelligence, it was written “communist” next to my name. So Bertoli knew me even better!

He was quite a tall man, around 35 year of age, not really accessible, not talkative, he was advocating Italian expansion to our areas through “its historic right”, but even we (resistance fighters) knew how appalled he personally was over Ustasha activities in SLANA, the information we heard from Marko Paro-Vidolin Kiža, whom I have already mentioned. In one critical moment when Ustashas were supposed to send several of us to SLANA, through Kiž we managed to prevent that decision due to personal disagreement, reproach, of Bertoli, who was basically a fascist, and who was friends with Ustasha Lovro Zubović and could be seen in the company of Ustasha priest Ljubo Magaš when he was in Pag.

Maybe he was forced into this two-faced game with his duty as a commander, but this is another proof of the official policy which let Ustashas do as they please. His, in this case, humane attitude, might have been just a part of some illusionary combination which never came through!

At that time we were in dire straits: we were covertly fighting the Ustashas, compromising them, firstly with the example of SLANA and the betrayal of the country, disrupting their mobilization and political constituency, then fighting equally the Italian aspirations towards Pag and disrupting their initial moves towards Italianization (for example, an event to express loyalty to Italy that was supposed to involve performances by the starving population, and having unemployed workers join “Fascio” together with their starving families…) at the same time we had to use our family connections to prevent Ustashas from taking us to the camp and equally to use other connections to influence the moral attitude of Bertoli for him not to support his associated Ustashas! Of course, such arrangements could not have lasted for a long time and were possible only in the beginning! But in the game of war, one day means a lot. After Bertoli, the commander of the garrison was reserve captain Aldo Roaldi, a bank clerk from Milan (or Turin), openly opposing the fascists, who did not take a single measure, both in regards to Italian political aspirations and in regards our activities on which he was informed (and we knew he was). Familiar with the past events in SLANA, he could not stand both Ustashas and his own Black Shirts. After Italy capitulated he was taken to a camp in Germany where he stayed until the end of the war. He was himself playing a game with his subordinates, some of which were declared fascists, giving us the sign that he was on our side.

I am talking about this because it shows the circumstances under which Ustashas were unable to commit yet another crime for which they had been preparing gladly, and under which circumstances, using pressure, wit, interventions of people, we managed to prevent four Orthodox Christians to be taken to SLANA, and another two to return. People were all over Felicinović and Uguić[4], who else than the organisers, not street sweepers for sure! Those who started everything were told to save people and it worked!

Further in the text we will shot how even the most heinous crime, with all its animal appetites and skill to wipe all trace, cannot be achieved. We will see that there is a living witness, an inmate who is alive today and who was in SLANA from that day it had been formed and almost until the end.

[1] Oren Ružić, Partisan fighter from Pag, later on the Ambassador of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (SFRJ) on Cuba, Chief of Protocol in SFRJ, died in 1988

[2] Ivo Bilić Duje, from Vranice near Split, a lighthouse keeper, a resistance fighter in Pag, a commander of Pag in 1943, later on the Commander of the Partisan Ship “PČ 4” (“Junak” – Hero), while with another ship he entered Trieste, later on a lighthouse keeper, died in 1972.

[3] Ferdo Radetić, President of the County War Crimes Commission for Croatian Coast.

[4] We will talk about them later in the book.