FOREWORD

The contents and topics of “CHARON AND DESTINIES” are historical literature on the Second World War which was initiated by nationalist and fascist ideas based on domination through liberation of your own people and enslavement of other peoples, through genocide and confiscation of property. Talking about the camp on the island of Pag, founded by the Ustasha authorities of so-called Independent State of Croatia (Nezavisna država Hrvatska – NDH), the book covers only the implementation of fascist Ustasha idea over Jews and Serbs in the first months of the persecution. The contents of the book do not cover the whole persecution over the territory of the war-time creation of NDH, but only gives details involving the Slana camp on Pag.

The author announced book’s contents with its title. In the name of CHARON, the boatman from the ancient Greek mythology who transported the dead over the river Styx, the author saw the reality of people transported from the mainland to the island in 1941, from their past life into the future death, people marked only with a sign of different religion or idea, prisoners and inmates of Ustasha prisons and camps.

It has been a long time since Charon transported the dead. But the DESTINY of this area, through Nazi and Ustasha “Legal provisions of the NDH”, decided on persecutions and exodus of people from their home soil and their death, turning our living neighbours, fellow citizens and villagers into the dead. This is where the first part of the title connects with the second, and Zemljar, through descriptions that these notions contain, shapes it into a book which, thus shaped, presents to us a part of historical events in 1941.

The author, Professor Ante Zemljar writes his texts using simple words and even literary sentences and style bringing closer to us, without mitigating them, all the horrors and events of those dark days during several months of 1941 in the Slana area on Pag.

While reading the material, taking into consideration both particular description of events and human destinies, and also historical and geographical descriptions and general contents, I felt the need and requested for this material to be published in the name of humanity, and for the sake of truthful and accurate reconstruction of these shocking events, so that this inhuman, twisted deeds are never repeated and always serve as warning should ever similar ideas appear.

Ante Zemljar, as a person who is familiar and has witnessed some of the events, started the expert and historical work on the reconstruction all events relating to the Slana camp. He found and kept discovering statements given a long time ago. As he tried to collect all of them and tried to describe what had already been described or known, he was met with silence that produced gaps. In his further investigation he tells the reader how he faced a “wall of silence” or “deceptions”, and finally the destruction of documents which was started as early as August and September 1941 by people who founded the camp and destroyed its inmates and buildings, and later on continued by their accomplices until this very day. Instead of stopping, satisfying himself with what he had already discovered, as many people were before him, with written and verbal statements talking about the committed evil or statements hiding something and deceiving us given from 1946 onwards, faced with countless problem he continues to search, he doubts, checks and investigates the crime that needs to be made public for the sake of truth. In the way of the investigation lay the passing of time, the crime committed and almost forgotten, the shame seen, told and experienced and everything else that tries to deny this evil. The author is aware of that and writes about it, but continues to find people and documents, he gets new statements and finds new historical sources.

When he realises he has nothing and nowhere else to look for he compiles texts, adds description and produces a book – a document on the Slana camp on Pag. The concept of the book is that of an investigative document covering statements, newspaper articles, documents and evildoers, and inviting more research. Events surrounding the Slana camp are now before readers and have become history.

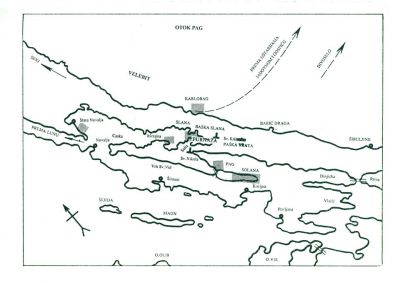

The reader is presented with geographical description of locations, first discussion in Pag on the location of the camp (out of sight but easily controlled), payment of transport from the mainland to the island and from the town to the camp, transport of camp inmates, their stay at the camp, possibilities and problems with building a camp, life of persecuted people, stories and legends of men and women from the camp, first deaths and first rescues.

The book is a commemoration to the persecuted people and those killed in the war.

While speaking about the camp and inmates the author talks also about geographical elements and economical factors in the town of Pag, but separates the crime from the local people and the area to which the Ustasha authorities gave and imposed the camp. The Pag islanders soon realised what the Ustasha authorities tried to achieve with their declared works – what sort of foundations did the camp inmates build with their bodies in the desolate area people call Slana. The people of Pag who were looking at the Ustasha camp, just like their neighbours from Rab who were looking at Italian camps being built, or people of Malok where also was a camp, never accepted that Nazi authority as their own. They were always looking forward to a future foretold by more progressive people from the islands, the future in which “principle” there was no room for a divide between people, but unity, brotherhood and equality.

With statements of participants who are still alive, the book further on describes the way in which the still existing documents were created, documents which are used to describe history.

Ante Zdjelar compares the memories of survivors with documents found in archives or with recorded old memories. In this “investigative document” is where the reader will find descriptions written down long ago, but only published recently (1985) in newspapers in series of articles on the Slana camp. Zemljar is creating a historical mosaic from all the statements, articles and descriptions. He confronts them and compares them before the reader and draws the truth from the confrontation between real facts and descriptions, or gives up on making conclusions, prevented with missing facts and the “wall of silence”.

Throughout the book we feel two aspects, the first historical and confirmed, and the one based on descriptions also used to find out the truth.

There is not a similar work amongst the books on Ustasha camps written and published here or in the world. This makes this book on war a unique one. It reads like a novel, so everything seems like a dream from another world and about other people and events. Everything is shocking, but the most shocking are documents written in the Slana camp by soldiers of the Italian occupying force. It is such a pity that these documents were made at the time when there were no more people left in the camp. The occupying force, its commission, examines, takes photographs of remains and describes crimes committed in Slana by Ustashas, their comrades and brothers in arms. At the same time there was an Italian camp on Rab for Jews and Slovenians. Are we ever going to find those testimonies and did Ustashas described Italian crimes?

During his research, Zemljar found records in Italian archives on photographs of the destroyed camp, and later on found those photographs in unmarked museum photo archives.

He adds those photographs to his book as documents of truth. To each photograph of a specific site in Slana taken at that time he adds one taken recently in order to show how the camp was destroyed in the same way how people and documents were.

Zemljar adds to the book another two pieces of art: a poem dedicated to the persecuted people and a painting as a vision of the truth about evil.

The clearest conclusion Zemljar makes is that this book does not finish the story on the Slana camp. There are still many leads and blanks. This book will initiate further research, because it incites interest. It will start initiatives to reconstruct what can be reconstructed, to compare what can be compared and to finally condemn what needs to be condemned.

Professor Ruda Polšak